We are still looking at the QUBO problem and trying to upgrade the Branch and Bound solver we have been writing. This post covers two things we have implemented, converting the whole thing to Rust and adding different (more intelligent) variable branching rules.

Rust Conversion

Here, we have actually moved the exact solver into the rust package we have been using for generating heuristics, hercules. The intention of this decision is to allow us to apply large k-opt optimization methods to improve the heuristic solutions, and in some instances (small) prove a solution is optimal. I will briefly give a general overview of the structure of the solver; we made some improvements to the modularity of the solver compared to the Python version. Some things are very similar, such as problem definition.

pub struct Qubo {

/// The Hessian of the QUBO problem

pub q: CsMat<f64>,

/// The linear term of the QUBO problem

pub c: Array1<f64>,

}

class QUBOProblem:

Q: numpy.ndarray # hessian of the QUBO problem

c: numpy.ndarray # linear term

When it comes to the definition of the Solver and the Nodes, a lot of fields were removed. This was because almost none of these fields were ever called, or they could be provided in another way without each individual component of the solver needing to have a reference to many of the other components. Nodes having a reference to the problem or their parents or children at least with the current implimentation is not nessisary. As the nodes only live inside the context of the solver, there is no need to be able to rebuild the entire problem + BB Tree from scratch from each node. This also greatly simplifies proving the memory safety of the overall program.

pub struct QuboBBNode {

pub lower_bound: f64,

pub solution: Array1<f64>,

pub fixed_variables: HashMap<usize, f64>,

}

class BBNode:

fixed: dict[int, float]

children: list[BBNode]

obj: float

sol: numpy.ndarray

problem: QUBOProblem

parent: BBNode

Structurally, almost everything else is the same; however, instead of passing functions defining the node selection and variable branching strategy of the solver, we are now using enums to define how we select these variables. Currently, only variable branching strategies are selectable, and the only node selection strategy is selecting the most recent node added. This is equivalent to a depth-first search. Similar to the heuristics work in the hercules package, a Python front end allows us to call the new rust solver from Python. A full implementation of the code can be seen in this file.

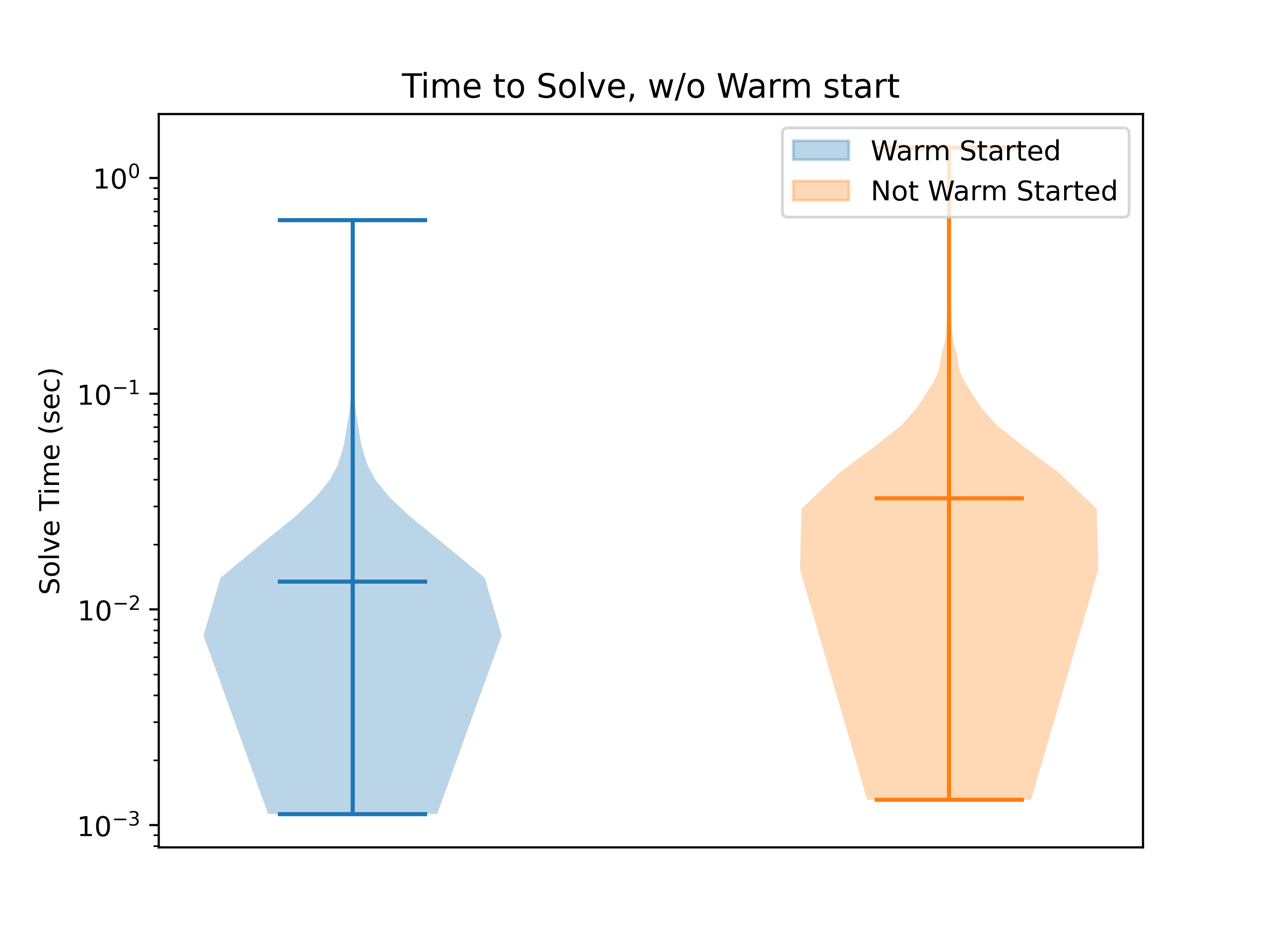

We can compare the performance between the Python and Rust versions with a random problem set. It is said that Rust is approximately 100 times faster than Python, but remember that most of what we are doing in the Python version is using numpy, which uses native/compiled code. So we shouldn’t expect to see THAT large of a difference between these two versions, but the overhead of copying the problems, calling the native code from Python, and other Python overhead might be significant. For this, we generated 100 problems with 30 variables each. Here, we can compare the distribution of solve times. Here, both are using the same node and branch selection methods, depth priority and first not fixed, respectively. Both use the QP solver, Clarabel, to solve the subproblems. Both are using persistence and the same warm start.

The first thing we immediately see is that the Rust version is obviously faster. The second thing we see is that the distribution is the same, just shifted down. On average, it is approximately 4.8 times faster. Not bad! The problem from the first post is that it took seconds and only takes milliseconds on equivalent hardware, so we know we are on the right path. We can look at different variable branching selection algorithms to see if we can further improve our average solve times.

Variable Branch Selection

So far, we have mostly been randomly selecting variables to branch on, and while this has actually proved to be effective (mostly due to the power of branch & bound), it is time to implement some smarter rules. Here, we will be comparing 5 different branching rules. We will give a brief description of each rule and the reasoning behind why we would want to use this method to speed up the problem.

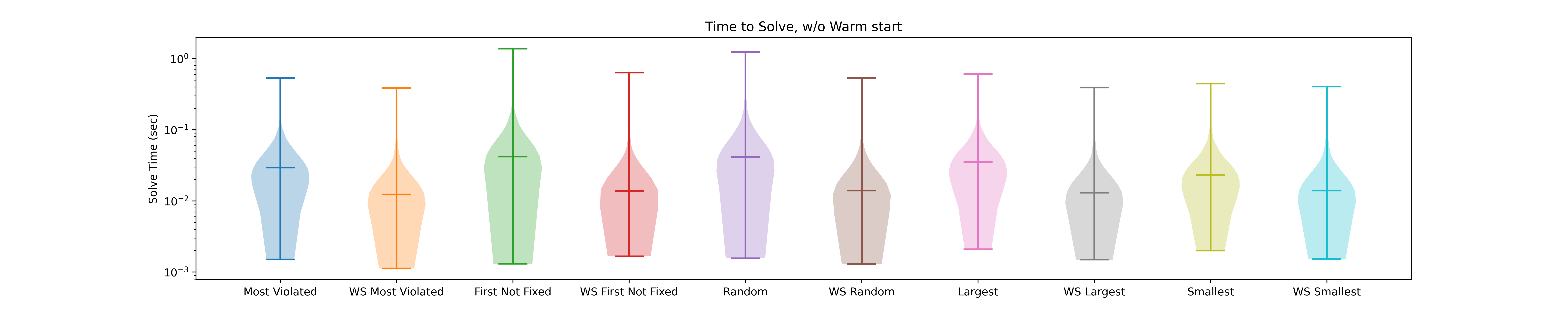

1) Most Violated Selection - Branches on the relaxed variable closest to 0.5. The idea behind this is that it tries to force integer feasibility as fast as possible. Studies in the literature show that this rule is not better than random selection in many MILP instances. 2) First Not Fixed Selection - Finds the first nonbranched variable. Similar to the above, the benefit of this rule is that it is almost immediate to compute, but again, it doesn’t consider problem structure. 3) Random Selection - There is not much else to say; this is one of the most basic rules. We will want to do this if we have no reason to expect any variable to be better to branch on than any other. 4) Largest Gain Selection - Branches on the variable predicted to raise the objective the most. If you think you already have the global solution, we are trying to remove the number of Nodes we need to explore. 5) Smallest Gain Selection - Branches on the variables predicted to raise the objective the least. If you don’t think you have the global solution, we are trying to take a greedy path towards the global solution.

To test the differences between these 5 branching rules, I made a set of 1000 problems with size 30 to check the effects of the branching strategy, with and without warm starting. For this, we solve each problem 10 times with different inputs, which is not something I would be willing to do with the Python version of the code. First, let’s compare warm starting v. not warm starting averaging in all our branching rules. Here, we get the result that warmstarting vs. not warmstarting gives us a speed-up of approximately 2.3x. This is with persistence fixing variables.

However, more interestingly, how do branching rules affect the solve time compared to each other? We can see the warm starting effects of different branching strategies differently. All improved, but some strategies are better than others on average. We actually see an interesting result here; while in a general setting, the most violated branching rule is ineffective, in my experience, it is the fastest strategy (at least on this problem set). On average, it is approximately 12% faster than the other strategies when warm starts. Without a warm start, the Smallest gain strategy is the most effective, which is in line with our expectations.

Wrap up

With the changes we discussed in this blog post, we reduced the time to solve the QUBO problems by 82% compared to the last post. If we compare against the solver described in the first post, we are approximately 2000 times faster (running both on my laptop). This is still quite a basic solver; compared to commercial solutions, this prototype still gets obliterated. For example, Gurobi solves these problems in presolve (This is incredible). To improve our solver’s performance, we can introduce an SDP subproblem solver, implied constraints, better preprocessing, and multithreading, to name a few.