Fourier series expansions are widely used as a problem-solving tool in engineering and other computational sciences. In effect, it is a simple expansion of orthonormal basis functions to approximate some original function. This is very useful for solving ordinary differential equations and partial differential equations, and the solutions created by using a Fourier series expansions is yet another Fourier series. The downside to this is that to evaluate this series is not always easy, nor does the series necessarily converge quickly. In many cases, the convergence of a series solution can be of order $\mathcal{O}(n^{-1})$, which means if we want 2 digit accuracy of our evaluated solution, we need to evaluate many of the terms of the series. This is not amenable to real-time computing, where a calculation must take as little time as possible and have a clear upper bound on time.

I have been reading Georgie Tolstov’s book, Fourier Series, and I came across an elegant and simple method for accelerating Fourier series to at least cubic convergence. By splitting the Fourier coefficient function into 2 functions, the slow converging function and the rapidly converging function, we can substitute in an identity for the slower converging section. Tables can be used to make this process quick. The downside is that the resulting accelerated series must be range reduced as the substituted function is not equal outside of the range.

Example 1

Here is an example of the method in action, let’s say we want to accelerate the following series.

\[f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{(n^3-1)sin(nx)}{n^4}\]By splitting the Fourier coefficient function into the fast a slow converging parts we get the following.

\[\frac{(n^3-1)}{n^4} = \frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n^4}\] \[f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{sin(nx)}{n}-\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{sin(nx)}{n^4}\]We can substitute identity for the first series and get a $\mathcal{O}(n^{-4})$ converging series instead of original $\mathcal{O}(n^{-1})$ converging series.

\[f(x) = \frac{\pi - x}{2}-\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{sin(nx)}{n^4}\]Example 2

Let’s do another example; this one is example 2, pg—145 from Tolstov’s book.

\[f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{(n^4-n^2+1)cos(nx)}{n^2(n^4+1)}\]The numerator is order 4, and the denominator is order 6, so this series converges quadratically, $\mathcal{O}(n^{-2})$. Here we can see that the Fourier coefficient can be split into a fast and a slow converging part that we can use to split the sum into 2 different sums.

\[\frac{(n^4-n^2+1)}{n^2(n^4+1)}= \frac{1}{n^2} + \frac{1}{n^4+1}\] \[f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{cos(nx)}{n^2} + \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{cos(nx)}{n^4+1}\]We can substitute in an identity for the first slow converging sum to get an $\mathcal{O}(n^{-4})$ converging series instead of the original $\mathcal{O}(n^{-2})$ converging series.

\[f(x) = \frac{3x^2-6\pi x-2\pi^2}{12} + \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{cos(nx)}{n^4+1}\]Numerical results

Let’s see how this pans out with computational speed-ups. Here I will be benchmarking with Python 3.7 using Numba. We will be looking at the first example.

import numpy

import numba

@numba.njit

def evaluate_series(x_points:numpy.ndarray, n:int)-> numpy.ndarray:

series = numpy.zeros_like(x_points)

for i in range(1, n):

coeff = 1/i - 1/i**4

series += coeff*numpy.sin(i*x_points)

return series

@numba.njit

def evaluate_series_accelerated(x_points: numpy.ndarray, n:int)-> numpy.ndarray:

#add in the identity

series = .5*(numpy.pi - x_points)

#fast converging series

for i in range(1, n):

coeff = -1.0/i**4

series += coeff*numpy.sin(i*x_points)

return series

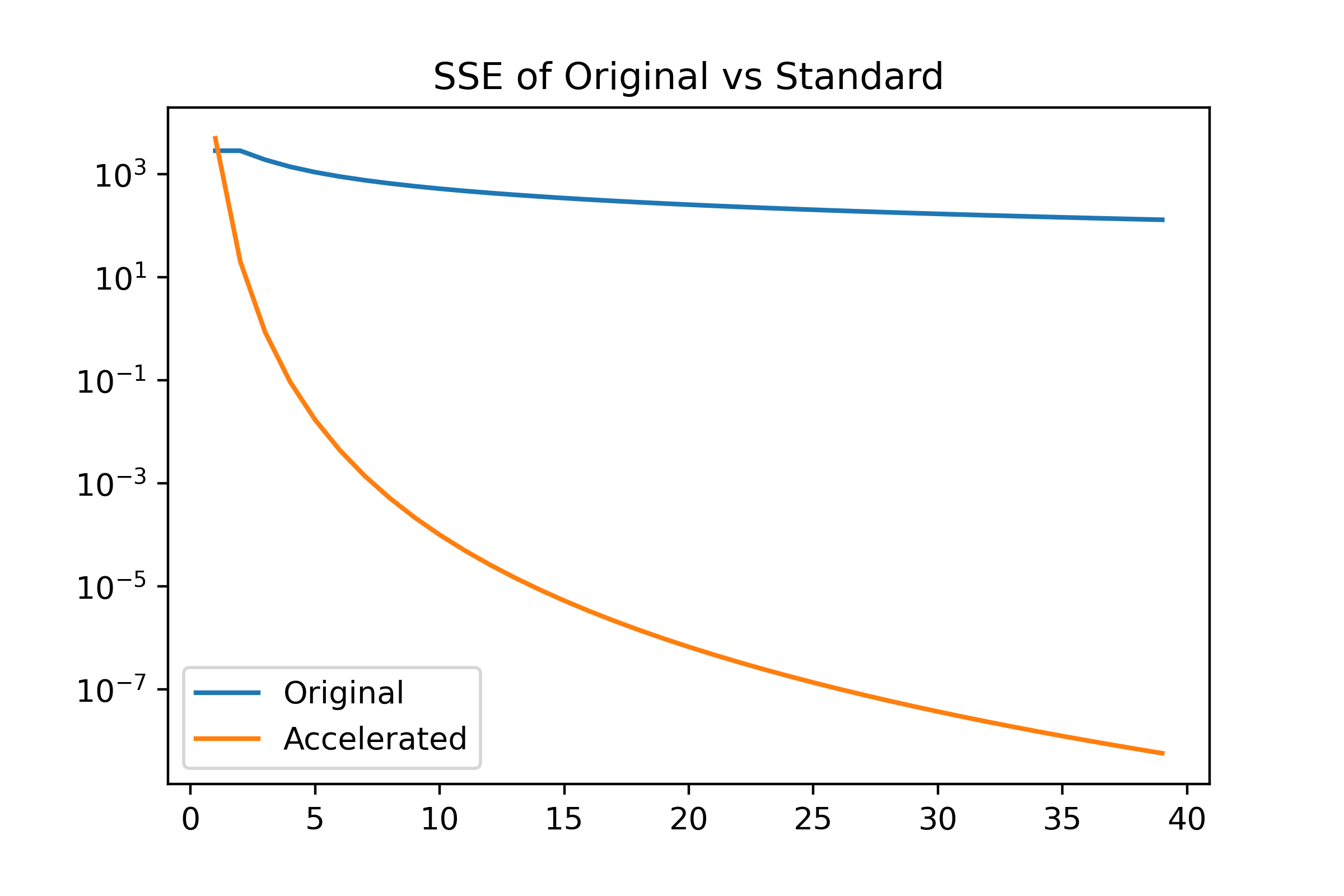

Here is the plot of the sum of squared errors of the original and the accelerated with ground truth. Taken with 10000 linear spaced points between 0 and $\pi/2$. As we can see, the accelerated series only needs a few terms to get to acceptable accuracy, while the unmodified takes many more orders of magnitude of terms to hit the same accuracy.